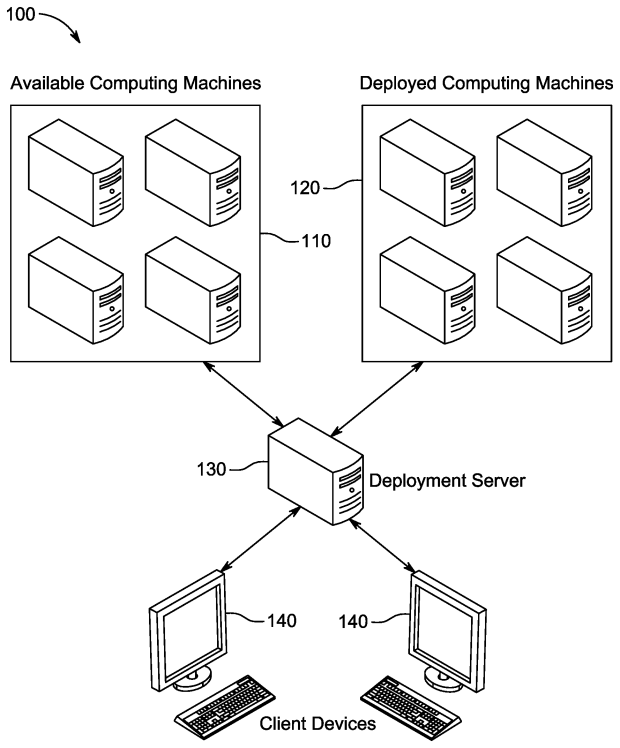

A while ago I was working on a system to handle network boot operations. The main server is written in Java, and I needed to be able to read contents out of ISO files. The easy solution would have been to extract the ISO to the hard drive. I was trying to avoid that to save space; and with all the different images, not have thousands of tiny files littering the drive.

Then I found stephenc repo (java-iso-tools) for reading ISO files in Java. This library worked great! It had examples which helped me get started, and was fast to dive though a file. It supported the traditional ISO-9660 formatted files, which I needed, and I was good to go. Years later, the people over at CentOS and Redhat Linux had the idea to start putting giant SHA hashes as file names. Suddenly the disc images I was getting contained filenames that were 128 characters in length; and sadly java-iso-tools was failing to parse these names. To explain why, we need a bit of a dive into how the ISO-9660 standard works.

ISO-9660 is Developed by ECMA (European Computer Manufacturers Association) as ECMA-119, and then was adopted into ISO-9660. Thus, technically I was able to get the standards documents and investigate how ECMA-119 worked. Images start with a header; pointing to several tables, and the root folder file. The information about files on the disc span out from that root file. The root file, is the root directory on the image. From there every file is either a directory (with/without children) or a file which can be read.

The standard has had many changes to it over the years. While the original ECMA-119/ISO-9660 standard dates back to the start of the CD-ROM, over time people added to the standard. With PC’s at the time running MS-DOS and being able to save files to a FAT file system as 8 letter then 3 letter for extensions, the formatted needed added onto so one day CentOS could have 128 character file names. Some early additions to the format were Rock Ridge, and the Enhanced tables. When reading the first bytes from an image, there are several byte blocks which state which version of the standard they work with; this was forward thinking in this way. The basic tables help simple devices easily be able to read the discs. They can offer short file names, and point to the same binary data other tables later do. Then the enhanced tables can offer more information, and be able to add additional features to the disc. Some of these features can include things like file permissions.

At this point I had decided I needed to fix the problem and was going to write my own library to do it. While it sounds crazy, I enjoy writing these low level libraries. I started with the ECMA-119 standard, and going through the flow, like I was a CD-ROM device reading an image. I would later add on code for Rock Ridge, and reading all the enhanced tables, and even adding on a UDF parser.

I don’t want to spend too much time going through the standard. If you are interested: ECMA-119/ISO 9660 Standard, ECMA-167/ISO_IEC 13346/Original UDF Standard, Rock Ridge, UDF 2.60, there is a collection of the standard documents in depth. This post is more to talk about the project in general, and how I enjoyed working on it. A few constraints I set upon myself were I wanted it to be 100% in Java 8. That way it could be natively compiled if someone wanted to do that, wouldn’t just be connecting to some native binary tool, and would work with older Java code bases. The project currently targets Java 11 being the LTS out at the time I was working on it. I know there are many code bases out there which are Java 8, and I actually dont think there is any code except some tests using Java 9+ features. If someone had a Java 8 project, they could remove the tests and compile to 8. We live in a little bit of an odd time now, where a project like this targets more enterprise users who tend to be back on older versions. And at the same time Java 24 is coming out. I wanted to give high level classes that a user needing a simple tool could use; but at the same time have deeper level objects publicly available.

I was using this in the earlier mentioned network booting environment.There I can be building 100+ servers at a time; speed, small, and fast code were important. I ended up adding as test some performance benchmarks. I test the old library as my control, then I do normal file lookups as well as pre-indexed. I developed a system where certain heuristics of the image are taken and can be stored. Then you can feed in this initial “vector” I called it, of the image and a file vector. If the image matched the initial vector for a few characteristics, we could reasonably assume its the same image originally scanned, then instead of reading all the header tables, we jump to the location of the file vector with trust. This does leave it up to the developer to make sure they are matching pre-indexed images with vectors; but if you do, you can much faster serve files.

This project was fairly straight forward to test, I had many and there are many ISO images out on the internet. And plenty of them are Linux Images! I also had the older library which I could use as a control to test against. I ended up writing many tests which help when people send Pull Requests to make sure nothing has broken. This project I needed done to support what I was working on. There were a few places where I didn’t fully flush out the metadata, but left it to the end user to, if they cared about that data type. I spent a lot of time in Hex Fiend hex editor marking segments and trying to understand where code I had was breaking down.

Over the years of working in Open Source, and going to a technical college, I have seen many strong technical projects that are very impressive code, and can do a ton of interesting things. And then the developer focuses on interesting things they can make their code do, and spends no time putting documentation together. At the same time there are many project that get the job done, but aren’t anything special; these projects put a few documents together and maybe an example, and then get all the usage. The area developers hate to spend time, but can be the most valuable is documentation. That pushed me to spend a lot of time commenting the code, and writing a large README file showing how to work with the library.

I hope you will take a look at the project, maybe use it, and feel free to drop issues as they arise! I have been using the library in production for years now. It doesn’t get a ton of updates, because there hasn’t been a lot I need to add to it. When a PR or Issue arise I take care of it. And with the project being published under my work, I get a lot of automated PRs to help upgrade the library.

Take a look! https://github.com/palantir/isofilereader